A Yes, a No, a straight line, a goal.

— Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols I.44

A Yes, a No; to fight, or write.

— Edmond Rostand, Cyrano de Bergerac

My soul, be satisfied with flowers

with weeds, with thorns even; but gather them

in the one garden you may call your own. ...

In a word, I am too proud to be a parasite;

and if my intellect lacks the germ that grows

towering to heaven like the mountain pine ...

I stand – not high, it may be – but alone.

“[Nietzsche was] equivocal about the nature of power. I assumed he really meant spiritual power, the conquest of nature, not power over others. He is very much like the Bible, he writes poetically, and you can take it as a metaphor or not; I took it metaphorically. I believed that the superior man could not be bothered enslaving others, that slavery is immoral, that to enslave his inferiors is an unworthy occupation for the heroic man.”

— Quoted in Barbara Branden, The Passion of Ayn Rand, p. 45.

Suppose that, in accordance with [Spencer’s] view, each muscle were to maintain that the nervous system had no right to interfere with its contraction, except to prevent it from hindering the contraction of another muscle; or each gland, that it had a right to secrete, so long as its secretion interfered with no other; suppose every separate cell left free to follow its own “interest,” and laissez-faire lord of all, what would become of the body physiological?

The fact is that the sovereign power of the body thinks for the physiological organism, acts for it, and rules the individual components with a rod of iron.

|

|

|

|

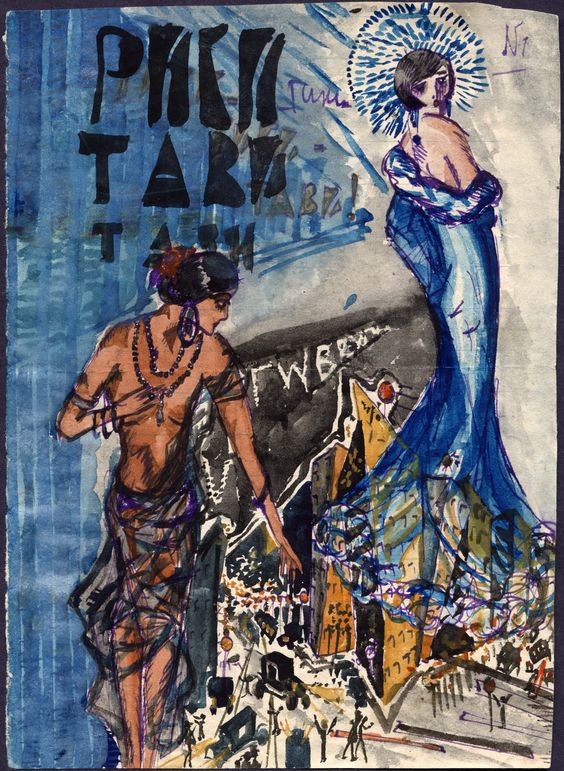

II.13: Between 1936 and 1940, Rand wrote several versions of a play based on We the Living. (The final version, under the title The Unconquered, was staged on Broadway in 1940, though less successfully than her previous Broadway outing, Night of January 16th. The first and last versions of the We the Living play, plus excerpts from the intermediate ones, were only recently published, likewise under the title The Unconquered.) In one of them, Andrei’s final speech references Hitler:

II.13: Between 1936 and 1940, Rand wrote several versions of a play based on We the Living. (The final version, under the title The Unconquered, was staged on Broadway in 1940, though less successfully than her previous Broadway outing, Night of January 16th. The first and last versions of the We the Living play, plus excerpts from the intermediate ones, were only recently published, likewise under the title The Unconquered.) In one of them, Andrei’s final speech references Hitler:

Comrades! Look at the world we’re facing! Do you see the seeds we planted sprouting abroad in new forms? In another country, close to us, there is a man, an obscure man who is rising. He is rising upon a principle he learned from us: Man is nothing, the State is all. What if he proclaims it under another color and another name? We were the first to say it! God forgive us, we were the first to say it! We brought a gift.

Let me go! – I’m still alive – You’ve taken most of it already. Once, when I was very young, I wanted to be an engineer, to work and to build. You’ve taken that. I had a friend and you made me betray him. You’ve taken that. I loved someone, someone who could have lived if he’d been born there, across the border. You’ve taken that. I have nothing left. Nothing but that I know I’m still alive and I can’t give up ....

Do you see what’s around us? Do you see them closing in on us? Do you see them staring, pointing, laughing at me? All the weak, the hopeless, the useless ones of the world! All the blind eyes, the shaking hands, the still-born souls! All the botched, icy-blooded ones who huddle their skins and their sweat together to keep warm enough to stay alive! You think you’ve won? You think you’ve broken me? But I’m laughing at you! I’m alive! Come on! Who’ll fight me first! Why do you shrink? There are so many of you and I’m alone! Or is that what’s frightening you? Alone! The only title, the only crown of glory one can wear today! Stand back, you poor, unborn ghosts! You can’t stop me! ....

I can walk. I’ll walk as long as I’m alive. I’ll fight you all as long as I’m alive! .... In the name of every living thing of every living world!