Zopyrus, who claimed to discern every man’s nature from his appearance, accused Socrates in company of a number of vices which he enumerated, and when he was ridiculed by the rest who said they failed to recognize such vices in Socrates, Socrates himself came to his rescue by saying that he was naturally inclined to the vices named, but had cast them out of him by the help of reason. (Tusculan Disputations 4.80)

Again, do we not read how Socrates was stigmatized by the physiognomist Zopyrus, who professed to discover men’s entire characters and natures from their body, eyes, face and brow? He said that Socrates was stupid and thick-witted, because he had not got hollows in the neck above the collar-bone – he used to say that these portions of his anatomy were blocked and topped up: he also added that he was addicted to women – at which Alcibiades is said to have given a loud guffaw! But it is possible that these defects may be due to natural causes; but their eradication and entire removal, recalling the man himself from the serious vices to which he was inclined, does not rest with natural causes, but with will, effort, training .... (On Fate 10-11)

This is the way I have travelled: Idealism singles men out from the world as unique, solipsism singles me alone out, and at last I see that I too belong with the rest of the world, and so on the one side nothing is left over, and on the other side, as unique, the world. In this way idealism leads to realism if it is strictly thought out. (Notebooks 1914-1916, p. 85)

Before I had studied Zen for thirty years, I saw mountains as mountains, and waters as waters. When I arrived at a more intimate knowledge, I came to the point where I saw that mountains are not mountains, and waters are not waters. But now that I have got its very substance I am at rest. For it’s just that I see mountains once again as mountains, and waters once again as waters.

For a similar move in a very different Buddhist tradition, see Georges Dreyfus’s book Recognizing Reality: Dharmakirti’s Philosophy and Its Tibetan Interpretations.

For a similar move in a very different Buddhist tradition, see Georges Dreyfus’s book Recognizing Reality: Dharmakirti’s Philosophy and Its Tibetan Interpretations.

After coming to America, Rand held various jobs in the Hollywood film industry, working inter alia as a movie extra on the set of The King of Kings, a script editor for Cecil B. DeMille, and head of the RKO wardrobe department. Rand wrote four plays (Ideal, Think Twice, Night of January 16th, and The Unconquered), the latter two of which were produced on Broadway; and she successfully sold five screenplays (Red Pawn, Top Secret, Love Letters, You Came Along, and her own adaptation of The Fountainhead), the latter three of which were filmed – and at the time of her death she had started work on a script for a tv miniseries adaptation of Atlas Shrugged. In addition, her fiction writing often has a cinematic quality (as in this line from Fountainhead I.8: “His shadow rose from under his heels, when he passed a light, and brushed a wall in a long black arc, like the sweep of a windshield wiper”).

After coming to America, Rand held various jobs in the Hollywood film industry, working inter alia as a movie extra on the set of The King of Kings, a script editor for Cecil B. DeMille, and head of the RKO wardrobe department. Rand wrote four plays (Ideal, Think Twice, Night of January 16th, and The Unconquered), the latter two of which were produced on Broadway; and she successfully sold five screenplays (Red Pawn, Top Secret, Love Letters, You Came Along, and her own adaptation of The Fountainhead), the latter three of which were filmed – and at the time of her death she had started work on a script for a tv miniseries adaptation of Atlas Shrugged. In addition, her fiction writing often has a cinematic quality (as in this line from Fountainhead I.8: “His shadow rose from under his heels, when he passed a light, and brushed a wall in a long black arc, like the sweep of a windshield wiper”).

“If all of you who look at me on the screen hear the things I say and worship me for them – where do I hear them? ... I want to see, real, living, and in the hours of my own days, that glory I create as an illusion! I want it real! I want to know that there is someone, somewhere, who wants it, too! Or else what is the use of seeing it, and working, and burning oneself for an impossible vision? A spirit, too, needs fuel. It can run dry.”

I live in my own light; I drink back into myself the flames that break out of me. I do not know the happiness of those who receive .... [T]his is my envy, that I see waiting eyes and the lit-up nights of longing. Oh, wretchedness of all givers! ... Oh, craving to crave! ... They receive from me, but do I touch their souls?

|  |  |

| Pola Negri | Greta Garbo | Marlene Dietrich |

Act I, Scene 1: Another of Rand’s favourite novelists was Sinclair Lewis; many of her minor characters (though never her main heroes) seem modeled on Lewis’s. In Act I, the repressed businessman George S. Perkins is likely based on George F. Babbitt, the main character in Lewis’s 1922 Babbitt and a minor character in his 1926 Elmer Gantry. (Babbitt is also a likely inspiration for Guy Francon in The Fountainhead – while Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here, a novel about the rise of folksy fascism in a future America, was an influence on Atlas Shrugged.)

Act I, Scene 1: Another of Rand’s favourite novelists was Sinclair Lewis; many of her minor characters (though never her main heroes) seem modeled on Lewis’s. In Act I, the repressed businessman George S. Perkins is likely based on George F. Babbitt, the main character in Lewis’s 1922 Babbitt and a minor character in his 1926 Elmer Gantry. (Babbitt is also a likely inspiration for Guy Francon in The Fountainhead – while Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here, a novel about the rise of folksy fascism in a future America, was an influence on Atlas Shrugged.)

Many of our bungalows have interesting histories as well: Elizabeth Taylor honeymooned with six of her eight husbands; Marilyn Monroe and Marlene Dietrich, among others, enjoyed them as well.

As I’ve mentioned earlier, Rand’s “Nietzschean phase” is characterised by four themes which will be rejected in her later writings:

As I’ve mentioned earlier, Rand’s “Nietzschean phase” is characterised by four themes which will be rejected in her later writings:

a) Innatism: treating superior character traits as largely inborn, and so necessarily restricted to a few, rather than something open to anyone to achieve.

b) Immoralism: treating those of superior character as exempt from ordinary moral rules.

c) Political elitism: more specifically, treating those of superior character as having the right to rule and dominate those of inferior character.

d) Subjectivism: an emphasis on will over reason, and on sheer personal preference over moral principle.

She can’t see anything in that window – only the silhouettes of people against the light. Only the shadows. And she sees this one man there – he’s tall and slender and he holds his shoulders as if he were giving orders to the whole world. And he moves as if that were a light and easy job for him to do. And she falls in love with him. With his shadow. ... And then, that evening, she is sitting alone on the roof, and there’s a shot, and that window is shattered, and that man leaps out onto her roof. She sees him for the first time – and this is the miracle: for once in her life, he is what she had wanted him to be, he looks as she had wanted him to look. But he has just committed a murder. I suppose it will have to be some kind of justifiable murder ... No! No! No! It’s not a justifiable murder at all. We don’t even know what it is – and she doesn’t know. But here is the dream, the impossible, the ideal – against the laws of the whole world. Her own truth – against all mankind. (Romantic Manifesto, pp. 181-182)

Ivar Kreuger |

William Hickman |

D.A.: – “Now tell us, didn’t Mr. Faulkner have a clear conception of the difference between right and wrong?”

KAREN ANDRE: – “Bjorn never thought of things as right or wrong. To him, it was only: you can or you can’t. He always could.”

D.A.: – “And yourself? Didn’t you object to helping him in all those crimes?”

KAREN ANDRE: – “To me, it was only: he wants or he doesn’t.”

I do not think, nor did I think it when I wrote this play, that a swindler is a heroic character or that a respectable banker is a villain. But for the purpose of dramatizing the conflict of independence versus conformity, a criminal – a social outcast – can be an eloquent symbol.

This, incidentally, is the reason of the profound appeal of the “noble crook” in fiction. He is the symbol of the rebel as such, regardless of the kind of society he rebels against, the symbol – for most people – of their vague, undefined, unrealized groping toward a concept, or a shadowy image, of man’s self-esteem.

That a career of crime is not, in fact, the way to implement one’s self-esteem, is irrelevant in sense-of-life terms. A sense of life is concerned primarily with consciousness, not with existence – or rather: with the way a man’s consciousness faces existence. It is concerned with a basic frame of mind, not with rules of conduct. If this play’s sense of life were to be verbalized, it would say, in effect: “Your life, your achievement, your happiness, your person are of paramount importance. Live up to your highest vision of yourself no matter what the circumstances you might encounter. An exalted view of self-esteem is a man's most admirable quality.”

How one is to live up to this vision – how this frame of mind is to be implemented in action and in reality – is a question that a sense of life cannot answer: that is the task of philosophy.

Night of January 16th is not a philosophical treatise on morality: that basic frame of mind (and its opposite) is all that I wanted to convey. (Night of January 16th, Introduction, pp. 2-3)

In Sienkiewicz’s Quo Vadis, the best-drawn, most colorful character, who dominates the novel, is Petronius, the symbol of Roman decadence – while Vinicius, the author’s hero, the symbol of the rise of Christianity, is a cardboard figure.

This phenomenon – the fascinating villain or colorful rogue, who steals the story and the drama from the anemic hero – is prevalent in the history of Romantic literature, serious or popular, from top to bottom. It is as if, under the dead crust of the altruist code officially adopted by mankind, an illicit, subterranean fire were boiling chaotically and erupting once in a while; forbidden to the hero, the fire of self-assertiveness burst forth from the apologetic ashes of a “villain.” (Romantic Manifesto, p. 115)

I stand here on the summit of the mountain. I lift my head and I spread my arms. This, my body and spirit, this is the end of the quest. I wished to know the meaning of things. I am the meaning. I wished to find a warrant for being. I need no warrant for being, and no word of sanction upon my being. I am the warrant and the sanction.

It is my eyes which see, and the sight of my eyes grants beauty to the earth. It is my ears which hear, and the hearing of my ears gives its song to the world. It is my mind which thinks, and the judgment of my mind is the only searchlight that can find the truth. It is my will which chooses, and the choice of my will is the only edict I must respect.

Many words have been granted me, and some are wise, and some are false, but only three are holy: “I will it!”

Equality 7-2521, after rediscovering the concept of the ego, declares that “the choice of my will is the only edict I must respect” – a stance that the later Rand would denounce as “whim-worship,” insisting on the normative primacy of reason over will. Likewise, Equality 7-2521’s declaration ... that among “my thought, my will, [and] my freedom,” the “greatest of these is freedom” parts company with the mature Rand, who would surely have said that the greatest of these is thought; after all, in her later years, she would explain: “I am not primarily an advocate of capitalism, but of egoism; and I am not primarily an advocate of egoism, but of reason.”

The protagonist’s courage, integrity, and intellectual curiosity are described in terms that imply that they are innate; for example, he describes himself as having been “born with a curse” that has “always driven us to thoughts which are forbidden.” Such a suggestion clashes with Rand’s later insistence on the decisive role of choice and habituation in determining one’s character.

The question is also debated, whether a man should love himself most, or some one else. People criticize those who love themselves most, and call them self-lovers, using this as an epithet of disgrace .... Those who use the term as one of reproach ascribe self-love to people who assign to themselves the greater share of wealth, honours, and bodily pleasures; for these are what most people desire, and busy themselves about as though they were the best of all things, which is the reason, too, why they become objects of competition. So those who are grasping with regard to these things gratify their appetites and in general their feelings and the irrational element of the soul; and most men are of this nature (which is the reason why the epithet has come to be used as it is – it takes its meaning from the prevailing type of self-love, which is a bad one); it is just, therefore, that men who are lovers of self in this way are reproached for being so.

That it is those who give themselves the preference in regard to objects of this sort that most people usually call lovers of self is plain; for if a man were always anxious that he himself, above all things, should act justly, temperately, or in accordance with any other of the virtues, and in general were always to try to secure for himself the honourable course, no one will call such a man a lover of self or blame him. But such a man would seem more than the other a lover of self; at all events he assigns to himself the things that are noblest and best, and gratifies the most authoritative element in and in all things obeys this; and just as a city or any other systematic whole is most properly identified with the most authoritative element in it, so is a man; and therefore the man who loves this and gratifies it is most of all a lover of self. ...

Therefore the good man should be a lover of self (for he will both himself profit by doing noble acts, and will benefit his fellows), but the wicked man should not; for he will hurt both himself and his neighbours, following as he does evil passions. (Nicomachen Ethics IX.8)

The Fountainhead explores architecture the way that Doktor Faustus explores musical composition or The Counterfeiters explores writing. But the novel is obviously about more than architecture – so much so that some critics have said that The Fountainhead isn’t interested in architecture at all, except as a metaphor for other things. But that’s too strong; Rand’s journals show an intense interest in architecture, and an enthusiasm in particular for both the designs and the theories of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. Rand spent half a year working as an unpaid assistant to modernist architect Ely Jacques Kahn in order to learn about the architecture business from the inside.

The Fountainhead explores architecture the way that Doktor Faustus explores musical composition or The Counterfeiters explores writing. But the novel is obviously about more than architecture – so much so that some critics have said that The Fountainhead isn’t interested in architecture at all, except as a metaphor for other things. But that’s too strong; Rand’s journals show an intense interest in architecture, and an enthusiasm in particular for both the designs and the theories of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. Rand spent half a year working as an unpaid assistant to modernist architect Ely Jacques Kahn in order to learn about the architecture business from the inside.

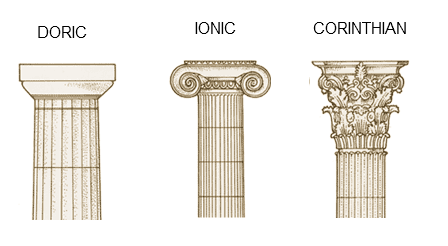

“A house can have integrity, just like a person ... and just as seldom. ... [Y]ou’ve seen buildings with columns that support nothing, with purposeless cornices, with pilasters, moldings, false arches, false windows. ... Do you understand the difference? Your house is made by its own needs. Those others are made by the need to impress. The determining motive of your house is in the house. The determining motive of the others is in the audience.”

They punish you for all your virtues. They forgive you entirely — your mistakes. Because you are gentle and just in disposition you say, “Guiltless are they in their small existence.” But their petty souls think, “Guilt is every great existence.” Even when you are gentle to them they still feel despised by you: and they return your benefaction with hidden malefactions.”

|  |

| Aristotle | Isabel Paterson |

But [honour] seems too superficial to be what we are looking for, since it is thought to depend on those who bestow honour rather than on him who receives it, but the good we divine to be something proper to a man and not easily taken from him. Further, men seem to pursue honour in order that they may be assured of their goodness; at least it is by men of practical wisdom that they seek to be honoured, and among those who know them ....

|  |

Never yet on earth has a human being laughed as he laughed! O my brothers, I heard a laughter that was no human laughter, and now a thirst gnaws at me, a longing that never grows still. My longing for this laughter gnaws at me ....

I saw a man once, when I was very young. He stood on a rock, high in the mountains. His arms were spread out and his body bent backward, and I could see him as an arc against the sky. He stood still and tense, like a string trembling to a note of ecstasy no man had ever heard. ... I have never known who he was. I knew only that this was what life should be. ... I’ve tried to renounce it. ... But I can’t forget the man on the rock.

|  |

| Thomas Hastings | Raymond Hood |

Here’s what I want out of life. If nobody had an automobile, I would not want one. If automobiles exist and some people don’t have them, I want an automobile. If some people have two automobiles, I want two automobiles.

|  |

| Sullivan | Wright |

I’ve read every word of The Fountainhead. Your thesis is the great one. Especially at this time. So I suppose you will be set up in the marketplace and burned for a witch. ... Your grasp of the architectural ins and outs of a degenerate profession astonishes me.

It was like a feudal establishment ... Almost all his students seemed like emotional, out-of-focus hero-worshippers. Anything he said was right, there was an atmosphere of worshipful, awed obedience. When he and I began to argue about something, the students were against me instantly; they bared their teeth that I was disagreeing with the master. They showed me some of their work, which was badly imitative of Wright. (quoted in Passion, pp. 157-8)

| Bragdon: | Rand: |

|---|---|

| He held the conviction that no architectural dictum, or tradition, or superstition, or habit, should stand in the way of realizing an honest architecture, based on well-defined needs and useful purposes: the function determining the form, the form expressing the function. … | He said only that the form of a building must follow its function; that the structure of a building is the key to its beauty; that new methods of construction demand new forms .... |

| Louis Sullivan has the distinction of having been, perhaps, the first squarely to face the expressional problem of the steel-framed skyscraper and to deal with it honestly and logically. ... To him the tallness of the skyscraper was not an embarrassment, but an inspiration – the force of altitude must be in it; it must be a proud and soaring thing, without a dissenting line from bottom to top. Accordingly, flushed with a fine creative frenzy, he flung upward his tiers and disposed his windows as necessity, not tradition, demanded, making the masonry appear what it had in fact become – a shell, a casing merely, the steel skeleton being sensed, so to speak, like bones beneath their layer of flesh. Then, over it all, he wove a web of beautiful ornament – flowers and frost, delicate as lace and strong as steel. ... | The explosion came with the birth of the skyscraper. ... Henry Cameron was among the first to understand this new miracle and to give it form. He was among the first and the few who accepted the truth that a tall building must look tall. While architects cursed, wondering how to make a twenty-story building look like an old brick mansion, while they used every horizontal device available in order to cheat it of its height, shrink it down to tradition, hide the shame of its steel, make it small, safe and ancient – Henry Cameron designed skyscrapers in straight, vertical lines, flaunting their steel and height. ... |

| Sullivan: | Rand: |

| It was deemed fitting by all the people that the four hundredth anniversary of the discovery of America by one Christopher Columbus, should be celebrated by a great World Exposition ... Chicago was ripe and ready for such an undertaking. ... It was to be called The White City by the Lake. ... The landscape work, in its genial distribution of lagoons, wooded islands, lawns, shrubbery and plantings, did much to soften an otherwise mechanical display ... |

The Columbian Exposition of Chicago opened in the year 1893. The Rome of two thousand years ago rose on the shores of Lake Michigan, a Rome improved by pieces of France, Spain, Athens and every style that followed it. It was a “Dream City” of columns, triumphal arches, blue lagoons, crystal fountains and popcorn. Its architects competed on who could steal best, from the oldest source and from the most sources at once. It spread before the eyes of a new country every structural crime ever committed in all the old ones. ... |

| The work completed, the gates thrown open 1 May, 1893, the crowds flowed in from every quarter .... These crowds were astonished. ... They went away, spreading again over the land, returning to their homes, each one of them carrying in the soul the shadow of the white cloud, each of them permeated by the most subtle and slow-acting of poisons .... Thus they departed joyously, carriers of contagion .... There came a violent outbreak of the Classic and the Renaissance in the East, which slowly spread westward, contaminating all that it touched, both at its source and outward ... through a process of vaccination with the lymph of every known European style, period and accident .... We have Tudor for colleges and residences; Roman for banks, and railway stations and libraries, or Greek if you like – some customers prefer the Ionic to the Doric. … |

It was white as a plague, and it spread as such. People came, looked, were astounded, and carried away with them, to the cities of America, the seeds of what they had seen. The seeds sprouted into weeds; into shingled post offices with Doric porticos, brick mansions with iron pediments, lofts made of twelve Parthenons piled on top of one another. The weeds grew and choked everything else. ... |

| Conan Doyle: | Rand: |

There was a tap at a door, a bull’s bellow from within, and I was face to face with the Professor. He sat in a rotating chair behind a broad table .... It was his size which took one’s breath away – his size and his imposing presence. ... He had the face and beard which I associate with an Assyrian bull; the former florid, the latter so black as almost to have a suspicion of blue, spade-shaped and rippling down over his chest. The hair was peculiar, plastered down in front in a long, curving wisp over his massive forehead. The eyes were blue-gray under great black tufts, very clear, very critical, and very masterful. A huge spread of shoulders and a chest like a barrel were the other parts of him which appeared above the table, save for two enormous hands covered with long black hair. This and a bellowing, roaring, rumbling voice made up my first impression of the notorious Professor Challenger. “Well?” said he, with a most insolent stare. “What now?” … “You were good enough to give me an appointment, sir,” said I, humbly, producing his envelope. ... “Oh, you are the young person who cannot understand plain English, are you? ... Well, at least you are better than that herd of swine in Vienna, whose gregarious grunt is, however, not more offensive than the isolated effort of the British hog.” He glared at me as the present representative of the beast. ... “... Well, sir, let us do what we can to curtail this visit, which can hardly be agreeable to you, and is inexpressibly irksome to me. ...” ... “It proves,” he roared, with a sudden blast of fury, “that you are the damnedest imposter in London – a vile, crawling journalist, who has no more science than he has decency in his composition!” He had sprung to his feet with a mad rage in his eyes. ... He was slowly advancing in a peculiarly menacing way ... “I have thrown several of you out of the house. You will be the fourth or fifth. Three pound fifteen each – that is how it averaged. Expensive, but very necessary. Now, sir, why should you not follow your brethren? I rather think you must.” He resumed his unpleasant and stealthy advance, pointing his toes as he walked, like a dancing master. (Conan Doyle, ch. 3) |

“Mr. Cameron, there’s a fellow outside says he’s looking for a job here.” Then a voice answered, a strong, clear voice that held no tones of age: “Why, the damn fool! Throw him out … Wait! Send him in!” … Henry Cameron sat at his desk at the end of a long, bare room. He sat bent forward, his forearms on the desk, his two hands closed before him. His hair and his beard were coal black, with coarse threads of white. The muscles of his short, thick neck bulged like ropes. He wore a white shirt with the sleeves rolled above the elbows; the bare arms were hard, heavy and brown. The flesh of his broad face was rigid, as if it had aged by compression. The eyes were dark, young, living. ... “What do you want?” snapped Cameron. “I should like to work for you,” said Roark quietly. ... “What infernal impudence made you presume that I’d want you? Have you decided that I’m so hard up that I’d throw the gates open for any punk who’d do me the honor? ... Great!” Cameron slapped the desk with his fist and laughed. “Splendid! You’re not good enough for the lice nest at Stanton, but you’ll work for Henry Cameron! ...” Cameron stared at him, his thick fingers drumming against the pile of drawings. ... “God damn you!” roared Cameron suddenly, leaning forward. “I didn’t ask you to come here! I don’t need any draftsmen! ... I’m perfectly happy with the drooling dolts I’ve got here, who never had anything and never will have and it makes no difference what becomes of them. That’s all I want. ... I don’t want to see you. I don’t like you. I don’t like your face. You look like an insufferable egotist. You’re impertinent. You’re too sure of yourself. Twenty years ago I’d have punched your face with the greatest of pleasure. You’re coming to work here tomorrow at nine o’clock sharp.” ... “Yes,” said Roark, rising. .... Roark extended his hand for the drawings. “Leave these here!” bellowed Cameron. “Now get out!” (Rand, I.3) |

|---|

|  |  |  |

| Lewis Mumford | Harold Laski | Heywood Broun | Clifton Fadiman |

He looked at the granite. To be cut, he thought, and made into walls. He looked at a tree. To be split and made into rafters. ... These rocks, he thought, are waiting for me; waiting for the drill, the dynamite and my voice; waiting to be split, ripped, pounded, reborn; waiting for the shape my hands will give them.

The house on the sketches had been designed not by Roark, but by the cliff on which it stood. It was as if the cliff had grown and completed itself and proclaimed the purpose for which it had been waiting.

Gold and silver, lead and copper, tawny iron ore – all lying in drift to yield themselves up to roaring furnaces and to flow obedient to the hand of the master mind ....

A building should appear to grow easily from its site ... Bring out the nature of the materials, let their nature intimately into your scheme.

She was utterly incapable of two things: of lying and of denying herself a desire; she did not quite grasp the possibility of either process. It was just as plausible to her to push her way through a crowd to see a steam shovel as it would have been to see a royal coronation; she would have enjoyed either. She had been spoiled and sheltered, accustomed to seeing her every wish granted; she had emerged from it completely sure of herself, neither arrogant nor offensive, but irresistible in the bright, innocent self-assurance of a person who had been spared all contact with pain. She acted as one would act if this were a dream world and life contained nothing to make lightness feel guilty and men were free to give beauty and significance to the insignificant gestures of their every moment. She was completely real in being unreal. ...

She was not afraid of Roark and she did not question the things she could not understand in him. She had not expected that she would love him, but she never needed reasons or explanations for the unexpected. He was not exactly like other people; she neither approved of it nor condemned it; she took it for granted; she never thought of resenting it, she was too avidly curious; and one universal trait had passed her by entirely; it never occurred to her, upon meeting anything strange or different, that that strangeness and difference were to be taken as some deep personal insult to her. She did not doubt herself; she had no compulsion to doubt others. (Journals, pp. 199-200)