|  |

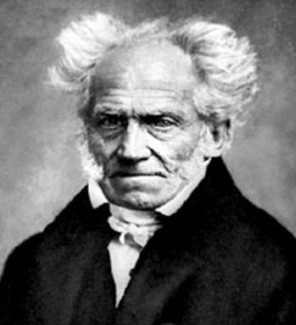

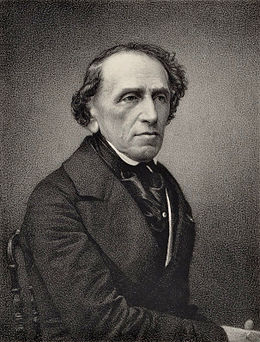

| Arthur Schopenhauer | Richard Wagner |

Day was departing, and the embrowned air

Released the animals that are on earth

From their fatigues; and I the only one

Made myself ready to sustain the war,

Both of the way and likewise of the woe,

Which memory that errs not shall retrace.

O Muses, O high genius, now assist me!

O memory, that didst write down what I saw,

Here thy nobility shall be manifest!

One day in February, 1865, Nietzsche was traveling alone to Cologne. He had allowed himself to be led by a porter to sights that were worth seeing and eventually asked him the way to a restaurant. But, instead, he was brought to a house of ill repute. “I saw myself,” Nietzsche told me later, “suddenly surrounded by a half dozen apparitions in spangle and gauze, who looked at me expectantly. I stood speechless for a while. Then I instinctively went to a piano, which was the only being with a soul in the gathering, and struck a chord. It loosened my stiffness, and I won my freedom.” From this and other things that I know about Nietzsche, I believe that the words that Steinhart said in a Latin biography of Plato can be applied to him: He never touched a woman.

|

|

|

| Julia Mann (the mother) | Julia Mann (the daughter) | Carla Mann |

Why this is hell, nor am I out of it.

Think’st thou that I who saw the face of God,

And tasted the eternal joys of Heaven,

Am not tormented with ten thousand hells,

In being depriv’d of everlasting bliss?

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have praised the purple vine,

My slaves should dig the vineyards,

And I would drink the wine;

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And his slaves grow lean and grey,

That he may drink some tepid milk

Exactly twice a day.

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have crowned Neaera’s curls,

And filled my life with love affairs,

My house with dancing girls;

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And to lecture rooms is forced,

Where his aunts, who are not married,

Demand to be divorced.

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have sent my armies forth,

And dragged behind my chariots

The Chieftains of the North.

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And he drives the dreary quill,

To lend the poor that funny cash

That makes them poorer still.

If I had been a Heathen,

I’d have piled my pyre on high,

And in a great red whirlwind

Gone roaring to the sky;

But Higgins is a Heathen,

And a richer man than I;

And they put him in an oven,

Just as if he were a pie.

Now who that runs can read it,

The riddle that I write,

Of why this poor old sinner,

Should sin without delight –?

But I, I cannot read it

(Although I run and run),

Of them that do not have the faith,

And will not have the fun.

Whoever yields, without reservation, to the brutal hypnosis of Wagner’s gestures and rhythms, has thus yielded to German imperialism. The genius of Lohengrin and Walkyrie is the genius of aggressiveness, reckless and gripping, ingeniously clever, for all its emotional exuberance. Nietzsche’s fight against Wagner anticipates and symbolizes the inexorable hate with which he would have persecuted Nazism. (Klaus Mann, André Gide and the Crisis of Modern Thought, p. 176)