|  |

| Jean Cocteau making himself handy | Marc Allégret with just the two hands |

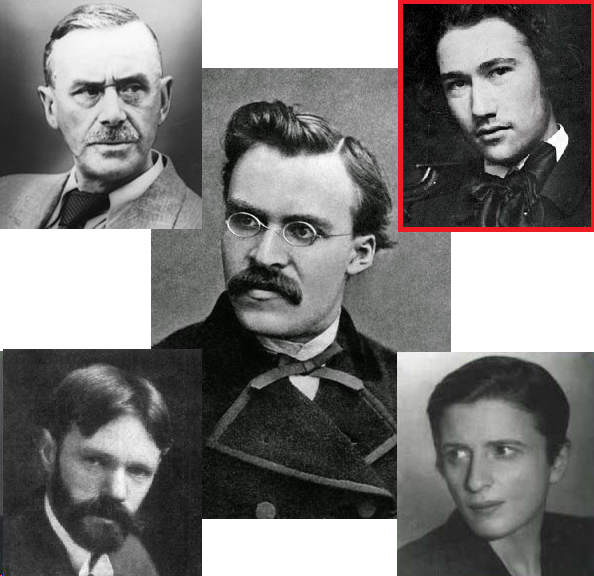

D. H. Lawrence, like most of the characters in his books, came from the coal-mining regions of central England (the Midlands), and more precisely Nottinghamshire. Like Nietzsche with Germany, Lawrence started out thinking of his task as the cultural regeneration of England, but later became disgusted with England (a feeling exacerbated by government censorship of his books, and government harassment of him personally during the First World War), preferring to live in Italy, Australia, or New Mexico. (Notice how in a 1912 letter he describes his mission to England in messianic terms even as he is inclining toward renouncing it: “Why, why, why was I born an Englishman? – my cursed, rotten-boned, pappy-hearted countrymen, why was I sent to them? Christ on the cross must have hated his countrymen.”)

D. H. Lawrence, like most of the characters in his books, came from the coal-mining regions of central England (the Midlands), and more precisely Nottinghamshire. Like Nietzsche with Germany, Lawrence started out thinking of his task as the cultural regeneration of England, but later became disgusted with England (a feeling exacerbated by government censorship of his books, and government harassment of him personally during the First World War), preferring to live in Italy, Australia, or New Mexico. (Notice how in a 1912 letter he describes his mission to England in messianic terms even as he is inclining toward renouncing it: “Why, why, why was I born an Englishman? – my cursed, rotten-boned, pappy-hearted countrymen, why was I sent to them? Christ on the cross must have hated his countrymen.”)

Thomas Mann seems to me the last sick sufferer from the complaint of Flaubert. The latter stood away from life as from leprosy. And Thomas Mann, like Flaubert, feels vaguely that he has in him something finer than ever physical life revealed. Physical life is a disordered corruption, against which he can fight with only one weapon, his fine aestheticism, his feeling for beauty, for perfection, for a certain fitness that soothes him, and gives him an inner pleasure, however corrupt the stuff of life may be. (Quoted in Icon Critical Guide, p. 61)

There is no doubt that a book of this kind has no right to exist. It is a deliberate denial of the soul that leavens matter. These people are not human beings. They are creatures who are immeasurably lower than the lowest animal in the Zoo. There is no kindness in them, no tenderness, no softness, no sweetness. ... Art is not anarchy. ... The artist is not his own law-giver. He must bow before the will of the generations of men. ... Life can be made very horrible and very hideous, but if literature aids and abets the business of making it horrible and hideous, then literature must perish. (quoted in Icon Critical Guide to The Rainbow and Women in Love, p. 18)

|  |

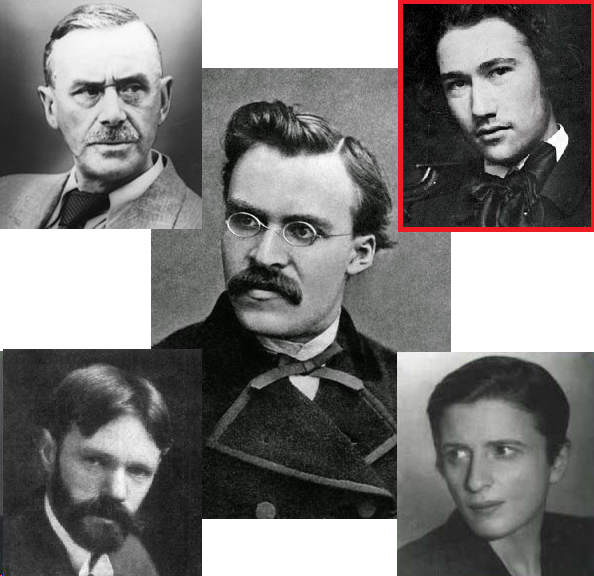

| Frieda (von Richthofen) Lawrence (Ursula) | Katherine Mansfield (Gudrun) |

Thus for Ursula. What about Gudrun? Well, in the Sigurd/Siegfried legend, after Sigurd’s death (and thus in the part of the story that Wagner ignores), his widow Gudrun/Gutrune/Kriemhild is persuaded by her brothers Gunnar/Gunther and Högni/Hagen to marry Atli/Etzel (i.e. Attila), the chieftain of the Huns. Later, when the brothers go to visit the newly married couple, hostilities break out and the Huns slaughter the brothers and their entourage. (This is based on an actual historical conflict in (again) the 5th century between the Huns and the Burgundian tribe led by king Gundahar (the basis for Gunnar), though well after Attila’s time.) Gudrun’s role in the massacre varies greatly between the Icelandic version (in the Völsungasaga and the Eddas) and the Germanic version (in the Nibelungenlied). In the Icelandic version, Attila is scheming against the Burgundians in order to obtain their treasure (the cursed Nibelung hoard); Gudrun is loyal to her family, and tries to get a warning to them not to accept Attila’s invitation; when her warning fails and her brothers are killed, Gudrun takes revenge by first feeding Attila’s sons to him (à la Atreus, Titus Andronicus, and Arya Stark), and then killing him. In the Germanic version, matters are more or less reversed: Attila has no hostile intentions toward the Burgundians, but Gudrun wants revenge against them for Sigurd’s death, so she manipulates the two sides into fighting and thereby engineers her brothers’ deaths, whereupon she is executed by one of Attila’s allies.

Thus for Ursula. What about Gudrun? Well, in the Sigurd/Siegfried legend, after Sigurd’s death (and thus in the part of the story that Wagner ignores), his widow Gudrun/Gutrune/Kriemhild is persuaded by her brothers Gunnar/Gunther and Högni/Hagen to marry Atli/Etzel (i.e. Attila), the chieftain of the Huns. Later, when the brothers go to visit the newly married couple, hostilities break out and the Huns slaughter the brothers and their entourage. (This is based on an actual historical conflict in (again) the 5th century between the Huns and the Burgundian tribe led by king Gundahar (the basis for Gunnar), though well after Attila’s time.) Gudrun’s role in the massacre varies greatly between the Icelandic version (in the Völsungasaga and the Eddas) and the Germanic version (in the Nibelungenlied). In the Icelandic version, Attila is scheming against the Burgundians in order to obtain their treasure (the cursed Nibelung hoard); Gudrun is loyal to her family, and tries to get a warning to them not to accept Attila’s invitation; when her warning fails and her brothers are killed, Gudrun takes revenge by first feeding Attila’s sons to him (à la Atreus, Titus Andronicus, and Arya Stark), and then killing him. In the Germanic version, matters are more or less reversed: Attila has no hostile intentions toward the Burgundians, but Gudrun wants revenge against them for Sigurd’s death, so she manipulates the two sides into fighting and thereby engineers her brothers’ deaths, whereupon she is executed by one of Attila’s allies.