Molinari-Proudhon Correspondence, 1858-1859by Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865) |

Molinari-Proudhon Correspondence, 1858-1859by Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865) |

|

[In 1858, Molinari and Proudhon were both living in Brussels, having relocated there in response to Napoléon III’s dictatorial regime in France. (Proudhon was on the run from the French authorities and had actually escaped from prison, whereas Molinari’s was more an exile of choice – an ideological statement – and he was able to make occasional visits to Paris, as we’ll see.) During this period, the two men knew each other and occasionally corresponded, and some of this correspondence is reproduced in vol. 16 of Molinari’s Œuvres Complètes (hard copy for sale here; free PDF download here), available as part of the Institut Coppet’s fantastic publication project.

I. Schaerbeek, 11 September 1858. Would you do me the pleasure of coming tomorrow (at 5:30) to share our modest dinner? It will be just the family at home, and if formal dinners are not to your taste you will meet with the kind of service you like. White trousers and black suits are entirely unknown in my neck of the woods. In short: come to my house in the same way that you go to that of my excellent friend Garnier, [Online editor’s note: Joseph Garnier (1813-1881); economist, statesman, and co-founder of the Société d’économie politique. – RTL] and come whenever it suits you – whenever you are bored with being alone yet do not care to be burdened with excessive conversation. Yours very sincerely. G. de Molinari. REPLY. Brussels, 11 September 1858. M. de Molinari,I find, upon returning home, your very friendly invitation, and I hasten to send you at one and the same time both my thanks and my excuses. I’ve just become booked up for tomorrow at 5:00, at the home of my upcoming publisher, Lebègue, with whom I must discuss mainly business. [Online editor’s note: Alphonse-Nicolas Lebègue (1814-1885), Belgian writer and publisher. – RTL] In the meantime I thank you for your hospitable thought; and I do not say – quite the contrary! – that, should you happen to be available in the evening after your dinner, I might not sometimes go and spend a little time at your place. I have worse than solitude: I have an absence of family, of books, of regular occupations – and hence boredom. Permit me to shake your hand most cordially. Yours very gratefully, P.-J. Proudhon. II. Friday, 17 September [1858]. My dear M. Proudhon.I have just received a letter from the Director of the journal Nord, who calls me to Paris. I will be leaving tomorrow at 2:45. If you have something you’d like to make known there that you prefer not to entrust to the post office – or if you would simply like to have news of your family from a witness de visu, [Online editor’s note: Latin, “firsthand,” “face-to-face.” – RTL] or finally if you would like me to bring you one of your charming young daughters, to relieve your boredom, I am entirely at your service. Yours sincerely, G. de Molinari III. 23 November 1858. My dear M. Proudhon.I forgot to tell you yesterday that the question of literary property was discussed in the last two sessions of the Société d’économie politique. You will perhaps not be sorry to read the reports of the sessions. Here they are. I also have at your disposal, if you want it, Laboulaye’s book and various articles from the [Journal des] Débats etc., on the Congress. [Online editor’s note: Édouard Laboulaye, (1811-1883), statesman, jurist, anti-slavery activist, and originator of the idea of presenting a Statue of Liberty to the United States. (Did anything ever come of that?) The book is presumably Laboulaye’s Studies on Literary Property in France and England (1858). The “Congress” would be the Congress on Literary and Artistic Property that was held in Brussels the same year. Molinari would later (1871-1876) become editor of the Journal des Débats. – RTL] Yours very sincerely, G. de Molinari IV. Monday, 14 February 1859. My dear M. Proudhon.Would you please give me, for the next issue of L’Économiste, [Online editor’s note: L’Économiste belge (1855-1868), a Brussels-based journal founded and edited by Molinari during his exile years. – RTL] an extract from your pamphlet (enough to fill two or three columns), selecting what will best suit the generally moderate temperament of my readers? That would give you reasonably good publicity. If you agree to take advantage of this offer, please send me the piece to be reproduced by Thursday at the latest. [Online editor’s note: I have but with a cursitory eye o’erglanced the issues of L’Économiste belge for February and March 1859, but I did not detect any contribution by Proudhon. – RTL] Yours very sincerely, G. de Molinari V. Brussels, 13 October 1859. My dear M. Proudhon.I hasten to give you in a few words the information you request. The history of the law of nations by Henri Wheaton [Online editor’s note: Henry Wheaton (1785-1848), American jurist, diplomat, and historian. The book to which Molinari refers is presumably Wheaton’s History of the Law of Nations in Europe and America (1845). – RTL] is excellent despite some rather lengthy and dull passages. You will find in his book both the history of ideas and the history of facts concerning the law of nations up to 1848. The author, an American, died two years ago. [Online editor’s note: Molinari is off by nearly a decade. – RTL] His book has been translated into French. I do not have it, but you can find it at the Bibliothèque Royale. Be sure to ask for the 2nd edition, which is much more complete than the 1st. [Online editor’s note: As far as I can determine, the first English edition of 1848 (later translated into French) was the second edition absolutely, as a shorter first edition appeared originally in French. – RTL] As for Martens’ Summary, it is a methodical overview of the rules of the law of nations generally in force. [Online editor’s note: Georg Friedrich von Martens (1756-1821), diplomat in the service of Russia; author of a Summary of the Modern European Law of Nations (1789). The “Martens Clause” is named after him. – RTL] These two works have the merit of dispensing with the need to read a host of others. I am sending you the two volumes by Martens. You will probably receive a visit from M. Mano, who asked me for your address. [Online editor’s note: G. A. Mano, author of several books on Asia. – RTL] See if it suits you to do business with him. It’s not to be dismissed lightly, it seems to me. But make sure you are well paid. Entirely yours, G. de Molinari. VI. Brussels, 21 October 1859. I called on you yesterday and was sorry not to find you in. I do not know whether you are inclined to do something for M. Mano, the director of the future Orient, but as I have absolutely no idea what his resources are (he has proven very uncommunicative on this point), I urge you not to extend him any credit. [Online editor’s note: According to a note by Benoît Malbranque, Mano was promoting a journal on Asian studies to be called L’Orient, but it never appeared. – RTL] It may be that my doubts about him are unfounded, but I confess, timeo danaos. [Online editor’s note: Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes, a Latin phrase from Vergil’s Æneid: “I fear the Greeks even when they bear gifts.” Possibly Molinari takes “Mano” to be short for the Greek name “Manos.” – RTL] So take precautions, and believe me yours very sincerely,G. de Molinari. |

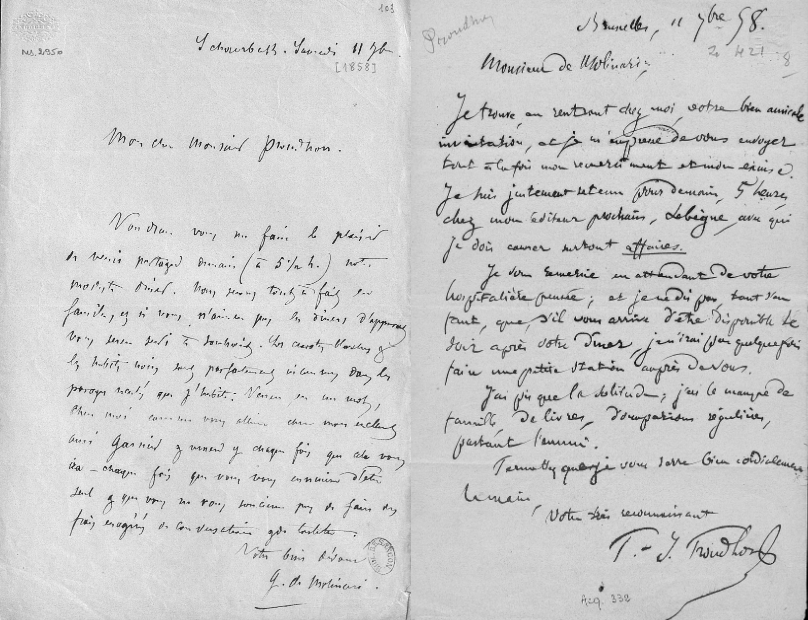

[Photo source: Ms. Z.421 and Ms. 2950, Fonds Proudhon, Besançon.]

Back to online library