Archives: May 2004

Thanks for Dying

Memorial Day is supposed to honour soldiers who died in our nation’s military adventures, just as Veterans’ Day is supposed to honour those who survived. Today we have the privilege of watching our rulers give earnest speeches expressing their “gratitude” to the victims of past policy even as they send thousands more to their deaths today.

Memorial Day is supposed to honour soldiers who died in our nation’s military adventures, just as Veterans’ Day is supposed to honour those who survived. Today we have the privilege of watching our rulers give earnest speeches expressing their “gratitude” to the victims of past policy even as they send thousands more to their deaths today.

As

Dunoyer, Spencer, Molinari, and Oppenheimer have taught us, war and the state are two sides of the same phenomenon – and the only true Memorial Day will be the day of their joint funeral.

I’ve blogged relatively little about the Iraq war lately; outrage fatigue, I guess. But Arthur Silber’s blog usually does a pretty good job of analysing the current insanity.

Posted May 31st, 2004 |

Convention Newsflash

[cross-posted at Liberty & Power]

I’ve just finished watching C-span’s coverage of the Libertarian Party convention. The three-way race for the top spot was the closest I’ve seen; most observers had been predicting a final showdown between Aaron Russo and Gary Nolan, but in a last-minute upset, Michael Badnarik squeaked through with the nomination. (A vice-presidential candidate had not yet been chosen when C-span’s coverage ended.)

I’ve just finished watching C-span’s coverage of the Libertarian Party convention. The three-way race for the top spot was the closest I’ve seen; most observers had been predicting a final showdown between Aaron Russo and Gary Nolan, but in a last-minute upset, Michael Badnarik squeaked through with the nomination. (A vice-presidential candidate had not yet been chosen when C-span’s coverage ended.)

While none of the three contenders has the glibness or the gravitas of Harry Browne, I had grown increasingly disenchanted with Russo, and Badnarik seems fine (a bit weak on abortion – perhaps he needs to read today’s post from Charles Johnson – but acceptable), so I am reasonably content with the outcome.

Badnarik for President!

Posted May 30th, 2004 |

Libertarianism in One Sentence

David Bergland once offered Libertarianism in One Lesson. I would like to offer libertarianism in one sentence.

The most succinct formulation of libertarianism I can think of is this:

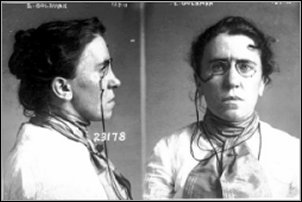

To every individual in nature is given an individual property by nature not to be invaded or usurped by any. For every one, as he is himself, so he has a self-propriety, else could he not be himself; and of this no second may presume to deprive any of without manifest violation and affront to the very principles of nature and of the rules of equity and justice between man and man. .... No man has power over my rights and liberties, and I over no man’s. I may be but an individual, enjoy my self and my self-propriety and may write myself no more than my self, or presume any further; if I do, I am an encroacher and an invader upon another man’s right .... every man by nature being a king, priest and prophet in his own natural circuit and compass, whereof no second may partake but by deputation, commission, and free consent from him whose natural right and freedom it is.Nor is this requirement lifted merely because you happen to be a police officer, or an elected legislator, or a member of a majority of citizens casting their votes. As Voltairine de Cleyre pointed out in 1890:

[A] body of voters can not give into your charge any rights but their own; by no possible jugglery of logic can they delegate the exercise of any function which they themselves do not control. If any individual on earth has a right to delegate his powers to whomsoever he chooses, then every other individual has an equal right; and if each has an equal right, then none can choose an agent for another, without that other’s consent. Therefore, if the power of government resides in the whole people, and out of that whole all but one elected you as their agent, you would still have no authority whatever to act for the one. The individuals composing the minority who did not appoint you have just the same rights and powers as those composing the majority who did; and if they prefer not to delegate them at all, then neither you, nor any one, has any authority whatever to coerce them into accepting you, or any one, as their agent ....I suggest that the phrase “Other people are not your property,” and variations thereon, might be a more useful tool of intellectual debate than some of the other slogans we more commonly use. Why not meet every new proposal to force people to do this or that with the protest “But you don’t own them,” “But they’re not your property”? At least this would reduce the issue to its essence.

Posted May 29th, 2004 |

Towards Standards of Criticism

It is often said that a purely aesthetic or critical appraisal of a work of art should in no way turn on an evaluation of the artist’s ideas, values, and commitments, but should take into account only the artist’s success in embodying those ideas, values, and commitments, whatever they may happen to be, in artistic form.

Even Rand, in The Romantic Manifesto, endorses what we may call the Neutrality Rule:

The fact that one agrees or disagrees with an artist’s philosophy is irrelevant to an esthetic appraisal of his work qua art. One does not have to agree with an artist (nor even to enjoy him) in order to evaluate his work. In essence, an objective evaluation requires that one identify the artist’s theme, the abstract meaning of his work (exclusively by identifying the evidence contained in the work and allowing no other, outside considerations), then evaluate the means by which he conveys it – i.e., taking his theme as criterion, evaluate the purely esthetic elements of the work, the technical mastery (or lack of it) with which he projects (or fails to project) his view of life.Of course Rand’s critical practice does not actually conform to this rule; within a few pages of the above quotation, for example, one finds her saying that when an artist “demand[s] sympathy for his monsters,” he thereby “crawl[s] outside the limits of the realm of values, including esthetic ones” – a judgment flatly inconsistent with the Neutrality Rule. Indeed, I would venture to affirm that scarcely any critic who advocates adherence to this rule actually succeeds in abiding by it with any great constancy.

The successful expression of a profound idea is simply a different animal from the successful expression of an insipid idea; it is not a gluing-together of two distinct and independently assessable components, an idea on the one hand and a content-neutral expressive technique on the other. Otherwise an artist who did a skilful job of expressing his own ideas and values would be equally skilful at expressing ideas and values alien to him – which is seldom true. (Rand’s story “The Simplest Thing in the World” is a good dramatisation of this fact.)

The successful expression of a profound idea is simply a different animal from the successful expression of an insipid idea; it is not a gluing-together of two distinct and independently assessable components, an idea on the one hand and a content-neutral expressive technique on the other. Otherwise an artist who did a skilful job of expressing his own ideas and values would be equally skilful at expressing ideas and values alien to him – which is seldom true. (Rand’s story “The Simplest Thing in the World” is a good dramatisation of this fact.)

Posted May 28th, 2004 |

Fogbound

[cross-posted at Liberty & Power]

The latest issue (Summer 2004) of the Laissez Faire Books catalogue carries, on p. 46, a condensed version of my article “Roads to Fascism: Sixty Years Later.” For the complete version, see here or here.

Lew Rockwell reminds us that while attention focuses on the Iraqi prisoners mistreated at Abu Ghraib, the thousands of Iraqi civilians slaughtered by U. S. troops pass unremarked in the press.

I’m off to London tomorrow – back in a week!

Posted May 17th, 2004 |

The Thin Blue Line

... that protects us from linguistic anarchy:

Maria Cobarrubias ... has built her general store into a profitable fixture in the Atlanta suburb of Norcross by catering to a growing Hispanic community.... Cobarrubias was stunned to receive a visit recently from the local marshal, who fined her for having a sign with the store’s name – Supermercado Jalisco – in Spanish. Supermercado is the Spanish word for supermarket, and Jalisco is the Mexican state where Cobarrubias was born. ...Moral: Your right to free speech ends where some cop’s inability to understand you begins.

Sgt. H. Smith, the Norcross marshal, said he has also issued citations to several Korean churches and an “Oriental beauty shop.” Some Spanish words are “acceptable,” he said, while others, such as “supermercado,” must be changed.

“The ‘super’ is English. But I don’t know what ‘mercado’ means,” he said. “If an American was out there driving by, he wouldn’t know what that was.”

– Washington Post, 6 February 1999

Posted May 17th, 2004 |

The Hoppriori Argument

In a number of publications (see his website), Hans-Hermann Hoppe has argued that the denial of libertarian self-ownership involves a performative contradiction. (A performative contradiction occurs whenever the act of asserting a proposition is incompatible with the truth, or justification, or both, of what is asserted; an example is the statement “Nothing is ever asserted.”)

Hoppe’s argument seems to inspire two principal sorts of reactions. Some find it an ironclad demonstration of the truth of libertarianism. Others find it a crazy, hopeless argumentative strategy that could never have had any chance of working.

My own response falls into neither category. I don’t think there’s any reason to reject out of hand the kind of argument that Hoppe tries to give; on the contrary, the idea that there might be some deep connection between libertarian rights and the requirements of rational discourse is one I find attractive and eminently plausible. (See my articles “Aristotle’s Conception of Freedom” (Review of Metaphysics 49 (June 1996), pp. 775-802), and “The Irrelevance of Responsibility” (Social Philosophy and Policy 16, no. 2 (Summer 1999), pp. 118-145).) But I am not convinced that the specific argument Hoppe gives us is successful.

Hoppe offers a number of different formulations of his argument; here is a condensed reconstruction of the argument as I understand it:

1. No position is rationally defensible unless it can be justified by argument.As noted, this is my wording of the argument, not Hoppe’s. If I have misunderstood Hoppe’s argument, which is quite possible, then my criticisms will be applicable only to my reconstruction of his position, and not to his position itself. But here at any rate is a first try.

2. No position can be justified by argument if it denies one or more of the preconditions of interpersonal argumentative exchange.

3. Interpersonal argumentative exchange requires that each participant in the exchange enjoy exclusive control over her own body.

4. To deny the right of self-ownership is to deny exclusive control over one’s own body.

5. Therefore, the denial of the right of self-ownership is rationally indefensible.

Posted May 15th, 2004 |

Faith of the Heart

What do the writers of Star Trek: Enterprise have against Vulcans?

The Vulcans used to be the coolest denizens of the Star Trek universe: aliens who, like the ancient Stoics, repressed their emotions in the name of an all-consuming devotion to rationality and logic. From an Aristotelean perspective, the notion that a commitment to reason involves the repression of emotion is of course a mistaken one; but there are worse mistakes one can make, and this one has at least a certain dignity and nobility. And that is indeed how Star Trek has always portrayed the Vulcan lifestyle: as admirable and noble, though tragically mistaken.

But the portrayal of Vulcans has taken a troubling turn on the latest Star Trek series. Vulcan repression of emotion is now presented less as a means to clarity of understanding and purpose, than as a mere response to psychological insecurity. The emphasis is all on repression and hardly at all on logic. Indeed, the Vulcans on Star Trek: Enterprise are represented as dogmatically refusing to acknowledge overwhelming evidence (e.g., of time travel) and as practising unjust discrimination against their own telepathic minority. On previous shows the Vulcans could often be arrogant and inflexible – but their conclusions were at least based on rational argument. The Vulcans also used to be scientifically curious, celebrating “infinite diversity in infinite combinations”; remember how Spock found everything “fascinating”? On the current show, however, the Vulcans display little curiosity, instead condemning the exploration of the unknown as risky and imprudent.

But the portrayal of Vulcans has taken a troubling turn on the latest Star Trek series. Vulcan repression of emotion is now presented less as a means to clarity of understanding and purpose, than as a mere response to psychological insecurity. The emphasis is all on repression and hardly at all on logic. Indeed, the Vulcans on Star Trek: Enterprise are represented as dogmatically refusing to acknowledge overwhelming evidence (e.g., of time travel) and as practising unjust discrimination against their own telepathic minority. On previous shows the Vulcans could often be arrogant and inflexible – but their conclusions were at least based on rational argument. The Vulcans also used to be scientifically curious, celebrating “infinite diversity in infinite combinations”; remember how Spock found everything “fascinating”? On the current show, however, the Vulcans display little curiosity, instead condemning the exploration of the unknown as risky and imprudent.

One might say in the show’s defense that Enterprise takes place about a century earlier than the original Star Trek; perhaps Vulcan society was (will be?) less advanced in that era. But that’s not a very plausible response; Vulcans have supposedly been following the Way of Surak more or less unchanged for centuries. I think it’s more likely that the Vulcan ideal simply doesn’t resonate at all with the current show’s writers.

This, after all, is the show whose theme song runs:

I’ve got faith of the heartAnd the crew of this Enterprise are the most whim-driven, touchy-feely, emotionally undisciplined set of Starfleet officers ever inflicted on a Star Trek audience. Everything about the show suggests that its current writers have a virtually reflexive commitment to emotionalism over reason. I suspect they portray Vulcans as dogmatic, intolerant, and timid because that’s what being “rational” means to them.

I’m going where my heart will take me

I’ve got faith to believe

I can do anything

I’ve got strength of the soul

no one’s gonna bend or break me

I can reach any star

I’ve got faith

I’ve got faith

faith of the heart

It’s no wonder, then, that they have done everything possible to undercut and weaken the show’s main Vulcan character, the female science officer T’pol. Partly this seems to be misogyny; the glorious days of Deep Space Nine and Voyager, when women and minorities got to play strong Trek characters, are definitely over. (Enterprise’s other female character does nothing but whine and sulk; the show’s one black character does nothing, period. Admittedly, most of the show’s white male characters are boring as hell too – and Captain Archer bears a creepy resemblance, in both face and voice, to the current U. S. President.) But I think it’s misovulcany as well.

It’s no wonder, then, that they have done everything possible to undercut and weaken the show’s main Vulcan character, the female science officer T’pol. Partly this seems to be misogyny; the glorious days of Deep Space Nine and Voyager, when women and minorities got to play strong Trek characters, are definitely over. (Enterprise’s other female character does nothing but whine and sulk; the show’s one black character does nothing, period. Admittedly, most of the show’s white male characters are boring as hell too – and Captain Archer bears a creepy resemblance, in both face and voice, to the current U. S. President.) But I think it’s misovulcany as well.

Posted May 14th, 2004 |

Are We All Consequentialists Now?

[cross-posted at Liberty & Power]

The current (June 2004) issue of Reason magazine carries the following letter to the editor. (I’ve restored my original formatting, plus a section – marked in brackets – that Reason deleted for space.)

To the Editor:One clarification: while I agree with Kant’s indictment of the consequentialist conception of morality as an instrumental strategy for promoting human welfare, I disagree with his remedy. For Kant, the solution is to sever the connection between morality and human welfare entirely; I instead follow the classical Greek tradition in tying the two together more closely, making morality an essential component of human welfare rather than a mere external means to it. For details see my book Reason and Value: Aristotle versus Rand; my articles Egoism and Anarchy and Why Does Justice Have Good Consequences?; and my review of Leland Yeager’s Ethics As Social Science.

In “Coercion vs. Consent” (March), Randy Barnett writes that “there are very few libertarians today for whom consequences are not ultimately the reason why they believe in liberty,” while Richard Epstein cheerfully agrees that libertarians are “all consequentialists now.”

Fortunately, it is not true that we libertarians are all consequentialists now. I say “fortunately,” because consequentialism is philosophically indefensible as a normative theory.

The basic problem with consequentialism is that it recognizes no limit in principle on what can be done to people in order to promote good consequences.

Now consequentialists insist that in the vast majority of cases, killing, torturing, or enslaving innocent people is not the best way to get good results. And of course they are right about that. But by the logic of their position the consistent consequentialist (happily a rara avis) must always be open to the possibility that killing, torturing, or enslaving the innocent might be called for under special circumstances, and this recognition necessarily taints the character of even one’s ordinary relations to other people.

[If the only reason I do not steal is that I’m afraid of being caught, then how am I morally superior to the thief? Likewise, if the only reason I don’t slaughter my neighbors is that doing so happens not to maximize social utility at the moment, then how am I morally superior to a mass murderer?]

As Immanuel Kant pointed out more than two centuries ago, to subordinate – or even to be prepared to subordinate – one’s fellow human beings to some end they do not share is to treat them as slaves, thereby denying both their inherent dignity and one’s own.Many consequentialists will say that they too can accommodate ironclad prohibitions on certain actions, on the grounds that utility will be maximized in the long run if people internalize such prohibitions. This is true, but it misses the point. Once one has internalized an ironclad prohibition, one is by definition no longer a consequentialist. One cannot treat certain values as absolute in practice and still meaningfully deny their absoluteness in theory; a belief that is not allowed to influence one's actions is no real belief. Most consequentialists are morally superior to their theory and, thankfully, pay it only lip service.

David Friedman is quite right to point out, in the same issue, that “concepts such as rights, property, and coercion” are complicated and not always susceptible to clear and easy rules. But this is not an argument for making consequences the sole test of right action. What it does mean is that non-consequentialist moral considerations establish only certain broad parameters, leaving it to consequences, custom, and context to make them more specific.

The parameters are not infinitely broad, however; and I do not see how they could be broad enough to license one group of people, called the government, to reassign title to the fruits of another group's labor at the first group’s sole discretion. Hence even if taxation and eminent domain had good results – which in the long term they rarely do – they would stand condemned on non-consequentialist grounds as slavery and plunder.

Roderick T. Long

Department of Philosophy

Auburn University

Auburn AL

Posted May 10th, 2004 |

Tolle, Lege

This list of books has been circulating through the blogosphere. I don’t know who compiled it, but one is supposed to post it with the titles of books one has read in boldface. Since I always comply with posted signs and placards, here’s my list:

BeowulfThe titles I haven’t read fall into the following four categories (not having read them, I am of course in no position to defend this classification):

Achebe, Chinua - Things Fall Apart

Agee, James - A Death in the Family

Austen, Jane - Pride and Prejudice

Baldwin, James - Go Tell It on the Mountain

Beckett, Samuel - Waiting for Godot

Bellow, Saul - The Adventures of Augie March

Brontë, Charlotte - Jane Eyre

Brontë, Emily - Wuthering Heights

Camus, Albert - The Stranger

Cather, Willa - Death Comes for the Archbishop

Chaucer, Geoffrey - The Canterbury Tales

Chekhov, Anton - The Cherry Orchard

Chopin, Kate - The Awakening

Conrad, Joseph - Heart of Darkness

Cooper, James Fenimore - The Last of the Mohicans

Crane, Stephen - The Red Badge of Courage

Dante - Inferno

de Cervantes, Miguel - Don Quixote

Defoe, Daniel - Robinson Crusoe

Dickens, Charles - A Tale of Two Cities

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor - Crime and Punishment

Douglass, Frederick - Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

Dreiser, Theodore - An American Tragedy

Dumas, Alexandre - The Three Musketeers

Eliot, George - The Mill on the Floss

Ellison, Ralph - Invisible Man

Emerson, Ralph Waldo - Selected Essays

Faulkner, William - As I Lay Dying

Faulkner, William - The Sound and the Fury

Fielding, Henry - Tom Jones

Fitzgerald, F. Scott - The Great Gatsby

Flaubert, Gustave - Madame Bovary

Ford, Ford Madox - The Good Soldier

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von - Faust

Golding, William - Lord of the Flies

Hardy, Thomas - Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Hawthorne, Nathaniel - The Scarlet Letter

Heller, Joseph - Catch 22

Hemingway, Ernest - A Farewell to Arms

Homer - The Iliad

Homer - The Odyssey

Hugo, Victor - The Hunchback of Notre Dame

Hurston, Zora Neale - Their Eyes Were Watching God

Huxley, Aldous - Brave New World

Ibsen, Henrik - A Doll’s House

James, Henry - The Portrait of a Lady

James, Henry - The Turn of the Screw

Joyce, James - A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

Kafka, Franz - The Metamorphosis

Kingston, Maxine Hong - The Woman Warrior

Lee, Harper - To Kill a Mockingbird

Lewis, Sinclair - Babbitt

London, Jack - The Call of the Wild

Mann, Thomas - The Magic Mountain

Marquez, Gabriel García - One Hundred Years of Solitude

Melville, Herman - Bartleby the Scrivener

Melville, Herman - Moby Dick

Miller, Arthur - The Crucible

Morrison, Toni - Beloved

O’Connor, Flannery - A Good Man is Hard to Find

O’Neill, Eugene - Long Day’s Journey into Night

Orwell, George - Animal Farm

Pasternak, Boris - Doctor Zhivago

Plath, Sylvia - The Bell Jar

Poe, Edgar Allan - Selected Tales

Proust, Marcel - Swann’s Way

Pynchon, Thomas - The Crying of Lot 49

Remarque, Erich Maria - All Quiet on the Western Front

Rostand, Edmond - Cyrano de Bergerac

Roth, Henry - Call It Sleep

Salinger, J.D. - The Catcher in the Rye

Shakespeare, William - Hamlet

Shakespeare, William - Macbeth

Shakespeare, William - A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Shakespeare, William - Romeo and Juliet

Shaw, George Bernard - Pygmalion

Shelley, Mary - Frankenstein

Silko, Leslie Marmon - Ceremony

Solzhenitsyn, Alexander - One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

Sophocles - Antigone

Sophocles - Oedipus Rex

Steinbeck, John - The Grapes of Wrath

Stevenson, Robert Louis - Treasure Island

Stowe, Harriet Beecher - Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Swift, Jonathan – Gulliver’s Travels

Thackeray, William - Vanity Fair

Thoreau, Henry David - Walden

Tolstoy, Leo - War and Peace

Turgenev, Ivan - Fathers and Sons

Twain, Mark - The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Voltaire - Candide

Vonnegut, Kurt Jr. - Slaughterhouse-Five

Walker, Alice - The Color Purple

Wharton, Edith - The House of Mirth

Welty, Eudora - Collected Stories

Whitman, Walt - Leaves of Grass

Wilde, Oscar - The Picture of Dorian Gray

Williams, Tennessee - The Glass Menagerie

Woolf, Virginia - To the Lighthouse

Wright, Richard - Native Son

Those I feel impelled, mostly by inclination, to read eventually: The Last of the Mohicans, The Red Badge of Courage, Don Quixote, The Great Gatsby, Madame Bovary, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Their Eyes Were Watching God, The Portrait of a Lady, The Magic Mountain, One Hundred Years of Solitude, War and Peace.

Those I feel impelled, mostly by duty, to read eventually: As I Lay Dying, The Sound and the Fury, Tom Jones, The Good Soldier, Catch 22, A Farewell to Arms, To Kill a Mockingbird, Beloved, All Quiet on the Western Front, The Catcher in the Rye, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Slaughterhouse-Five, Native Son.

Those I do not feel particularly compelled ever to read: A Death in the Family, Go Tell It on the Mountain, The Adventures of Augie March, An American Tragedy, Long Day’s Journey into Night, Doctor Zhivago [though I loved the movie], The Bell Jar, The Crying of Lot 49, Call It Sleep, The Color Purple.

Those I never heard of before this list: The Woman Warrior, Ceremony.

Posted May 8th, 2004 |

Let’s Do the Time Warp Again

Guess who’s to blame for the mistreatment of Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib.

Would you believe – feminists and gays?

Yep, George Neumayr of The American Spectator explains it all for us. An evil lesbian force field, generated at the March for Women’s Lives in DC last month, traveled backwards in time and apparently hit Abu Ghraib prison like Frank N. Furter’s sonic transducer on a Saturday night.

I am not making this up.

Oddly enough, it also turns out, apparently, that the same evil lesbian force field has long been in charge of the Texas prison system. I look forward to Neumayr’s explanation of this curious turn of events.

But like the man said: it’s astounding; time is fleeting; madness takes its toll ....

Posted May 8th, 2004 |

No War, No State, No War Between the States

The following letter appeared in this morning’s Opelika-Auburn News:

To the Editor:For more on this subject, see my blog entry Shades of Grey (and Blue) from last year.

Proponents of the Union often seem to think the Civil War was almost entirely about slavery, while proponents of the Confederacy often seem to think it had almost nothing to do with slavery.

I highly recommend to both sides historian Jeffrey Rogers Hummel’s book Emancipating Slaves, Enslaving Free Men. He makes a persuasive case for what is, alas, the interpretation least flattering to both sides: the desire to extend the institution of slavery to the western territories was one of the South's chief reasons for seceding, while antislavery sentiment was not at all central to the North's reasons for trying to prevent secession.

Both sides were fond of quoting the Declaration of Independence – yet hypocritically so. The South claimed the right to secede from the Union, but denied slaves the right to secede from their masters. Abraham Lincoln for his part declared that he would hold the Southern states in the Union by force even if slavery were abolished. Neither position can be squared with the Declaration’s emphasis on the “consent of the governed.”

There certainly were people with admirable motives on both sides of the Civil War – but for the most part such folks were exploited by, rather than influential on, their respective political leaderships. It’s time we stopped romanticising a bloody conflict that was waged for largely ignoble reasons on both sides. “Lost Cause,” “Won Cause” – either way, an unjust cause.

Roderick T. Long

Posted May 8th, 2004 |

No Thinking, Please

Just caught a clip on MSNBC of Guy Womack, attorney for one of the soldiers accused of mistreating prisoners in Iraq. He was giving the usual “just following orders” defense; when interviewer Deborah Norville raised the question of the Nuremberg Trials, he answered: “We don’t want soldiers in war to debate philosophical issues.”

Maybe we should start wanting that?

A good start would be to give each new recruit a copy of Stanley Milgram’s Obedience to Authority.

Posted May 4th, 2004 |

Separate But Equal?

The articles to which Edmonds points me do not relieve my worries about the implications of the outlook he endorses. Edmonds’ defense of chivalry seems to me to neglect the way that the “code of chivalrous conduct” has served to reinforce social perceptions of female helplessness and dependence. As individualist anarchist Victor Yarros pointed out during those glorious 1800s, the “privileges and special homage accorded by the bourgeois world to women” are really “marks of woman’s degradation and slavery.”

The articles to which Edmonds points me do not relieve my worries about the implications of the outlook he endorses. Edmonds’ defense of chivalry seems to me to neglect the way that the “code of chivalrous conduct” has served to reinforce social perceptions of female helplessness and dependence. As individualist anarchist Victor Yarros pointed out during those glorious 1800s, the “privileges and special homage accorded by the bourgeois world to women” are really “marks of woman’s degradation and slavery.”

Posted May 3rd, 2004 |

Anti-Feminism Is Anti-Liberty

Brad Edmonds has followed up his column on Real Men vs. Progressive Men (see my reply here) with a sequel, Real Women vs. Feminist Women.

I won’t go through his new list point by point, because, well, ugh. But I can’t resist responding to the accompanying commentary.

Edmonds expresses surprise that his first column was attacked for expressing “disrespect for women,” since he had “said nothing at all about women.” Now, c’mon. When someone writes that “real men” prefer one-career families to two-career families, and attacks day care to boot, it’s pretty obvious that he is defending traditional gender roles.

This time around he tells us:

Notice I included armpits and legs for women, but did not mention body parts for men. … Women are supposed to be pretty, and just about all of them can be if they want. Men are supposed to be strong, and just about all of them can be if they want.Let’s think about what this entails. Women are supposed to specialise in a trait that is primarily about being pleasing to others; men are supposed to specialise in a trait that is primarily about being useful to oneself. It’s hard to see how it could be any more obvious that this sort of ideology can only serve to rationalise and reinforce the exploitation of one half of the human race by the other half. Just as statism perpetuates itself by inculcating the myth of the necessity and virtue of government, so patriarchy perpetuates itself by inculcating traditional sex roles.

Posted May 3rd, 2004 |

Finding the Brake

In his 1815 Principles of Politics, French liberal author Benjamin Constant defended the monarch’s “right to dissolve representative assemblies.”

Constant’s position might seem surprising. Wasn’t securing the independence of parliaments from the royal will one of liberalism’s hard-won victories?

His reasoning ran as follows. The “tendency of assemblies to multiply indefinitely the number of laws” is the inevitable result of “two natural inclinations in the legislators, the need to act, and the pleasure of believing themselves necessary.” Hence it is only to be expected that legislators should “share out amongst themselves human existence, by right of conquest, in the same way as Alexander’s generals shared out the world.” The function of the monarch is to serve as a check against this tendency. This is why the political executive is customarily entrusted with the power of vetoing legislation; but, Constant maintains, the veto is not enough:

His reasoning ran as follows. The “tendency of assemblies to multiply indefinitely the number of laws” is the inevitable result of “two natural inclinations in the legislators, the need to act, and the pleasure of believing themselves necessary.” Hence it is only to be expected that legislators should “share out amongst themselves human existence, by right of conquest, in the same way as Alexander’s generals shared out the world.” The function of the monarch is to serve as a check against this tendency. This is why the political executive is customarily entrusted with the power of vetoing legislation; but, Constant maintains, the veto is not enough:

The veto is precisely a direct means of repressing the indiscreet activity of representative assemblies but, when employed too often, it irritates without disarming them. Thus dissolution is the only remedy whose effectiveness is assured.But what ensures that the monarch will use this power beneficently rather than mischievously? Here Constant’s argument becomes less compelling: as a “neutral power” rather than an “active power,” the monarch has, or should have, only the power to restrain the actions of other parts of the government, but no power to initiate action himself; as a “being apart at the summit of the pyramid,” the monarch floats serenely above the fray rather than becoming involved in partisanship, and serves only to mediate among the different branches of government.

It is not the troops on horseback, it is not the companies afoot, it is not arms that defend the tyrant. This does not seem credible on first thought, but it is nevertheless true that there are only four or five who maintain the dictator, four or five who keep the country in bondage to him. Five or six have always had access to his ear, and have either gone to him of their own accord, or else have been summoned by him, to be accomplices in his cruelties, companions in his pleausres, panders to his lusts, and sharers in his plunders. These six manage their chief so successfully that he comes to be held accountable not only for his own misdeeds but even for theirs. The six have six hundred who profit under them, and with the six hundred they do what they have accomplished with their tyrant. The six hundred maintain under them six thousand, whom they promote in rank, upon whom they confer the government of provinces or the direction of finances, in order that they may serve as instruments of avarice and cruelty, executing orders at the proper time and working such havoc all around that they could not last except under the shadow of the six hundred, nor be exempt from law and punishment except through their influence. ... And whoever is pleased to unwind the skein will observe that not the six thousand but a hundred thousand, and even millions, cling to the tyrant by this cord to which they are tied.In light of La Boétie’s analysis, Constant’s ideal monarch turns out to resemble the Randian fantasy of government as a reliable, impersonal robot. The braking function cannot be assigned to the monarch, because a monarch must either participate in faction or remain aloof; but if he remains aloof he lacks the power to serve as a brake, while if he participates in faction he cannot brake the activities he is simultaneously abetting.

The property of mass is inertia. In politics, inertia is the veto. A function or factor can only be found where it is. No plan or edict can establish it where it is not. ... [In the Roman Republic] the tribunes of the people [were] invested with the formal veto power. ... At one time, the tribunes of the people ‘stopped the whole machine of government’ for a number of years, refusing to approve and thus permit any act of government whatever ... until their grievances were redressed. They were able to do so because the power they exercised did inhere in the body they represented. It was there. If the people will not move the government cannot act. Though laws are passed and orders given, if mass inertia is found opposed, the laws and orders will not be carried out. ... [T]he function of mass, which is taken for granted by mechanical engineers, and usually ignored by political theorists, was understood by the Romans. They used it where it belongs for stability, by attaching to it directly that part of the mechanism proper to the factor of inertia, the device to ‘cut’ the motor when necessary.How is this “mass inertia veto” to be institutionally realised? Paterson maintains that by vesting the “power of the purse” in the House of Representatives, the U.S. Constitution ensures that the ability to cut off the fuel on which the government operates is assigned to the democratic element. The problem with this solution, however, is that congressional representatives are government functionaries, invested with the power of initiating legislative action and not merely of restraining the actions of other parts of government. With regard to the tendency of legislatures “to multiply indefinitely the number of laws,” the House of Representatives is obviously not the solution; it’s part of the problem.

Posted May 2nd, 2004 |